Bill Ronald used to call me sometimes in the middle of the night. He wasn’t drunk, or if he was, it was a drunkenness born not so much of booze as it was of his almost childlike excitement about his own art and the passionately lived life that was bringing it forth.

I remember his calling me at three in the morning (I think it was in the summer of 1994). He was phoning about a large painting of his, a vast, vertical work (about eight feet high) in washy blacks and creams and dark reds, that I had admired earlier that day in his studio. It was a rushing, fluid work, with lots of spray-painted pigment running down the canvas like raindrops sluicing down a windowpane.

“You know that big cream painting you liked today?” he asks me. “Yeh, it’s a terrific painting.” “Well,” says Bill, “I think you should buy it!” “I can’t do that,” I tell him. “I can’t afford it. It’s $8500.00!!” He pauses for a second or two to consider this unexpected hitch. Then he comes up with a simple, obvious solution to this dismal, clerical difficulty of mine. “I tell you what,” he says. “You take the painting and pay me a hundred dollars a month for the rest of your life!!!!” I didn’t take him up on this rapturous offer. I always wish I had.

To call William Ronald larger than life would be almost offensively obvious—like calling a locomotive heavy or a banana split fattening. Ronald was like the crown prince of a small, showy duchy—of which he was the only inhabitant.

I fondly remember his paroxysms of showmanship: the pink, sequined capes he’d wear, the green cowboy boots, the old Rolls-Royce he drove majestically through the city, the jazz combos jamming while he worked, and, sometimes, the gaggles of semi-naked young muse-women who would drape themselves about his studio, inevitably playing second fiddle to whatever was happening on the canvas in front of him.

I have quite a few Ronalds in my collection—because he gave them to me. He’d give me a wild little painting every time I’d visit him in his studio. I loved to watch him paint. It was like watching a dog go swimming and then shake himself dry. He’d paint and we’d talk and at the end of it, he’d hand me this little wet, glistening picture and I’d carry it home on my knees in a taxi—like a hot pizza.

He wasn’t always William Ronald. He was born William Ronald Smith in Stratford, Ontario in 1926. It was while he was an only middling and very shy student at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto in the late 1940s (working nights at an aircraft factory to pay his tuition) that he decided to drop the “Smith” part of his name and suddenly be reborn as just William Ronald (his brother, the excellent painter John Meredith Smith, also became simply “John Meredith” at this same time). According to Ronald, the name change was epiphanic. As he told a friend at the time, “I would say that people who are really screwed up should change their names!” With one clerical stroke, this abrupt change of identity appears to have both banished his shyness and vanquished his wasteful tendencies to depression, somehow lending him a certain permission, as it were, to become fully what he had always wanted to be: a thunderclap of a painter—brash, inventive and more or less fearless in the studio.

In 1952, while swimming upstream as a raucously abstract painter against the slow-flowing river of a more academic kind of art promulgated by O.C.A., Ronald still managed, somehow, to win a couple of prizes that year amounting to several thousand dollars. It was his favourite teacher, the painter Jock Macdonald (still greatly undervalued, in my estimation), who suggested that Ronald use the money to travel to New York and sign up for summer art classes with the legendary abstract-expressionist painter Hans Hofmann. The lordly Hofmann liked the young man’s work, and Ronald returned to Toronto in the autumn of 1952 with what one acquaintance rather decorously termed “a significantly larger self-image than when he had left.”

It was an enhanced self-image that was now, at last, seamlessly congruent with the bravura paintings Ronald was already making—such as the rugged yet graceful, calligraphically deft, Slow Movement (1952), purchased by the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa, Ontario, in 1971.

Widespread acclaim followed quickly. Ronald’s suggestion that Simpson’s department store in Toronto deliberately exhibit abstract paintings in their window displays of furniture resulted in the store’s watershed 1953 exhibition, Abstracts at Home, which led, in turn, to the founding in October of 1953—largely by Ronald—of Canada’s first abstract painting collective, Painters Eleven (which rhymed mellifluously with—though in opposition to—“The Group of Seven”). Painters Eleven embraced Canadian abstraction with a dynamic, theatrical confidence echoed in their cheeky, bristling manifesto: “There is no jury but time.”

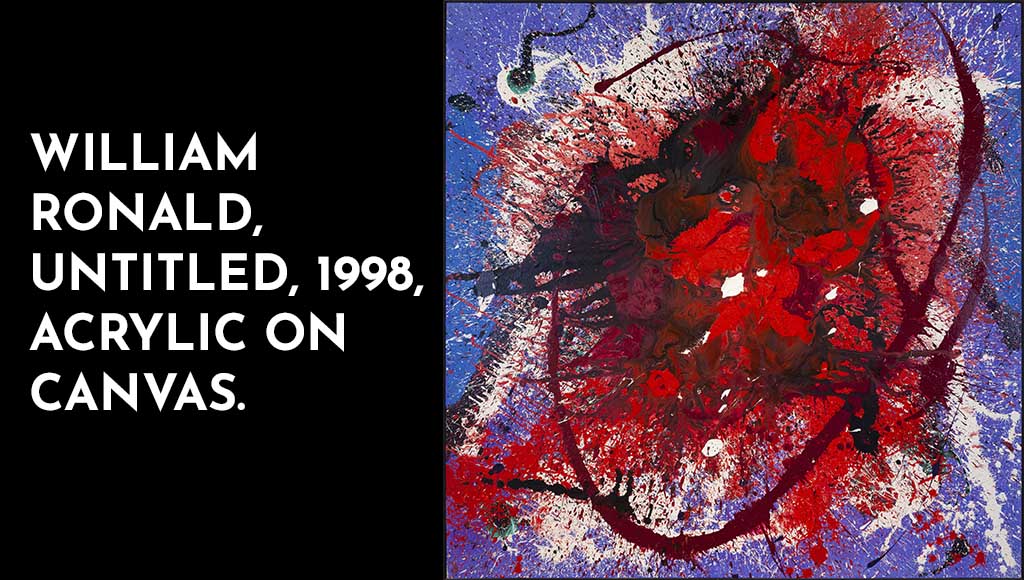

– William Ronald, Untitled, 1998, acrylic on canvas

All the members of Painters Eleven would soon be quickly gathered into the annals of Canadian art history: William Ronald, Jock Macdonald, Harold Town, Jack Bush, Oscar Cahen, Hortense Gordon, Tom Hodgson, Ray Mead, Alexandra Luke, Walter Yarwood, and Kazuo Nakamura.

By 1956, Ronald was back in New York, suddenly finding himself under contract to the prestigious Kootz Gallery, where he was now rubbing shoulders with abstract-expressionist art stars like Franz Kline, the aforementioned Hans Hofmann, Mark Rothko and what Ronald characterized as “all those goddam legends. I was so young and beautiful at the time,” he said, disarmingly, “and so ignorant.”

Ronald was exhibiting, swaggering, selling, and generally thriving. It was a heady period, but it didn’t last. All art movements are malleable and modifiable and adjustable. And by around 1962, the hegemony of abstract-expressionism was being toppled everywhere by Colour-field painting, Hard-edge painting, Pop art, Op art, Minimalism and Conceptual art. Ronald’s gusty, crash-and-burn abstractionism was suddenly out. He tried (foolishly, I think) to paint using clean, clear colours and hard, careful edges, but it just didn’t work. It wasn’t like him.

By 1965, William Ronald was back in Toronto. Everyone thought he’d stopped painting but he hadn’t. Though for some reason—possibly for the money, possibly because Ronald always needed an audience—he suddenly began doing a lot of radio and TV: a radically eccentric CBC TV show called The Umbrella in 1966, co-hosting CBC Radio’s As It Happens (1968-69) and, maddest of all, an all-night wallow in TV-mayhem called Free For All on Toronto’s Citytv (1972-74) where, sometimes, he made paintings live on camera. Whatever gets you through the night. By 1974 he was back in his studio for good. He made big paintings that jostled madly with worm-like lengths of pigment straight from the tube. He wantonly spray-painted canvases. He also made some mostly unseen masterworks like Comedian (1983) and Arrival (1992).

He made mistakes, of course. But at least they were large-scale, gloriously offensive mistakes, the most epic of which was his labouring at the sixteen huge paintings comprising his Prime Ministers Series, begun in 1977 and completed seven years later in 1984. All of themare, in my estimation, relentlessly awful (the Pierre Elliott Trudeau work was the best and it’s terrible too). Bill wanted a million dollars for the entiresuite. I don’t recall his getting it. In 1993, a patron-collector named Irving Zucker did finally buy the paintings and give them to the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. I don’t know if he paid a million bucks for them.

Most stories of dazzling early success in painting are tales outlining a brief trajectory of fame and glory followed by a slow protracted burn-out. Happily, this didn’t happen with Ronald. Although increasingly hobbled by bouts of ill-health including arthritis and a serious heart attack in 1990 precipitated, no doubt, by bouts of heavy drinking and a losing struggle with obesity—he soldiered on masterfully in the studio, making paintings that were among the most gleefully unruly and urgently volcanic of his entire career.

The large untitled painting reproduced here is the last painting William Ronald made. It was painted in 1998, mere hours before the heart-attack that killed him. In a catalogue to the exhibition of these last magnificent works, published in 2000 by Toronto’s Christopher Cutts Gallery, I wrote about this great benediction of a painting: “…the centre has been flayed into a violent absence – ending as a tilted, rust-red oval, wobbling like a decaying orbit around a white-hot, axle-like point of pure light…there is only painted energy.” I think this is the way a painter’s world ought to end—not with a whimper, but with a majestic Big Bang.

Gary Michael Dault

Credit: Christopher Cutts Gallery

Title Image: Ronald’s studio as it was at the time of his death, February 9, 1998 (photo by John Reeves)