Airplanes and adventure have captivated men—and women for centuries. Despite this shared passion, men dominate the industry as airline pilots, flight instructors, maintenance and aerospace engineers, and in management positions. Though the past four years have seen a tremendous increase in female student pilots, the worldwide average for women employed in commercial aviation continues to hover at a dismally low 6-7%.

Transport Canada statistics indicate that in 2007, 497 women (4.5%) held Airline Transport Pilot Licenses compared to 10,813 men; in 2018, the number of female pilots had increased to 761 compared to 12,834 male pilots, and now represented 5.9%. Statistics for American pilots compiled by the Pilot Institute (2022) indicate only 8,206 (4.92%) women hold an Airline Transport Pilot License, the highest category attainable, compared to 166,738 men. When all categories (student, recreational, sport, private, commercial, and airline transport) are tallied, female pilots number 72,428 (9.57%).

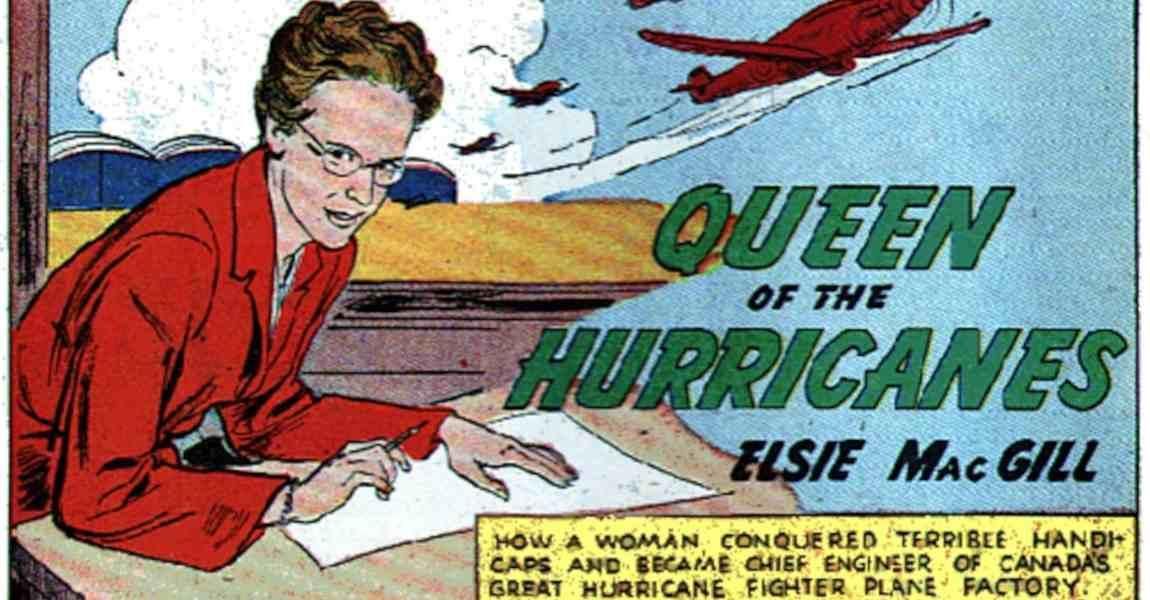

Canada’s first licensed female pilot, Eileen Vollick, earned her wings on March 13, 1928. The following year, Florence ‘Pancho’ Barnes started working as Hollywood’s first stunt pilot and Amelia Earhart plus ninety-eight other females formed the Ninety-Nines. That same year, Canada’s Elsie MacGill became the first North American1 woman to earn a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. To honour her achievement, the Royal Canadian Mint’s 2023 commemorative coin celebrates MacGill as the ‘Queen of the Hurricanes,’ a woman who believed we can all soar higher, given the chance.

Despite the outstanding success of many women, aviation became segregated by gender during the Golden Age of Aviation. With few exceptions, men earned money by flying air mail routes and transporting passengers for the emerging aviation industry. In contrast, most women were restricted by law, and public opinion, to fly as stewardesses or to participate in private endeavors such as air races, aerial daredevil performances, the setting of speed, endurance, and altitude records.

An exception to aviation’s gender segregation was Helen Richey who, in addition to setting altitude and endurance records, became the first woman to fly a scheduled commercial airline in USA and the first female air mail pilot. Hired in 1934 by Pennsylvania’s Central Airlines, her career was blockaded when the all-male pilot union refused to accept her and persuaded the FAA to restrict Richey’s flights to daytime and good weather. Today, this would be constructive dismissal but, as the lone female and without today’s collegial support or legal recourse, Richey quit after Central Airlines allowed her only twelve round trips in ten months.

When WWII started in 1939, Canadian Vi Milstead earned her private pilot license and joined Richey and hundreds of other female pilots on all continents except Antarctica, in military organizations called the WASPs (Women’s Air Service Pilots, USA) and British Commonwealth ATAs (Air Transport Auxiliary Pilots). These women flight-tested new aircraft, ferried planes to military training bases, flew damaged aircraft to maintenance facilities, and flew solo in planes designed for two pilots. Without their contributions to the war effort, male pilots would not have had airplanes to fly combat missions—and WWII may have ended very differently.

At the war’s end, companies refused to retain women in their wartime roles, forcing them to return to gender ’appropriate’ roles as wives and mothers. Particularly egregious was the treatment of women of Richey’s caliber and experience. Despite her record-setting performances, ten-thousand-hours of flight time, and wartime service with the British ATA and the American WASPs, Richey was one of many unable to pursue their dream because airlines, populated and operated by men, believed aviation jobs belonged to men. Impoverished and emotionally devastated, Richey committed suicide in 1947.

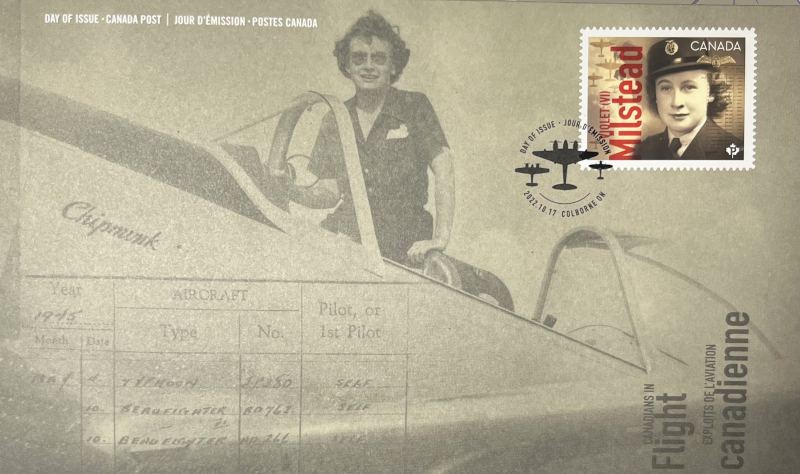

Milstead, one of Canada’s first professional female pilots, joined Great Britain’s Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) and flew forty-seven different types of military planes. After the war, she returned to Canada as a flight instructor. Watch Vi’s story at Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame and The Vi Milstead Story (Heritage Cramahe, video by Sean Scally).

Image #1: Canada Post stamp/poster Vi Milstead 2022, Colborne, Ontario.

The advent of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the late 1960s encouraged women to explore non-traditional roles and careers and, in 1973, nearly four decades after Richey’s strangled commercial career, women broke into commercial aviation. Canadian Rosella Bjornson and American Emily Howell Warner became the first North American women hired by major air carriers.

Statistics compiled by Captain Jenny Beatty using information from the US DOT, FAA, and the Institute for Women in Aviation Worldwide, indicates that in 1960 only 4,218 (1.67% of total pilot population) of American women were licensed pilots but a decade later, that number had increased to 13,685 (2.55%), representing a 224% increase; in 1980, the number almost doubled to 26,895 (4.29%).

Since the 1980s, approximately 10-11% of students have been female. Data compiled by America’s Pilot Institute indicates that 42,184 females enrolled as student pilots in 2022 compared to 14,580 female students in 2015, a phenomenal increase of 189%. However, these numbers have not translated into comparable statistics for commercially employed female pilots.

In addition to the pressures of expensive flight training and conflicting obligations of family, school or work experienced by most student pilots, female pilots historically received inadequate encouragement or social support. The Women in Aviation Advisory Board, founded by the FAA in 2018, determined that women choose aviation careers less frequently than men because of gender-unique social pressures and systemic societal barriers. Behaviour is gendered, with a double standard of appropriate conduct defined by and different for gender, and with the most rules, restrictions, and social punishments assigned to females.

An increased number of female aviators has heightened the awareness that gender stereotypes serve to perpetuate inequalities. Within their Human Resource departments, many companies have developed family friendly policies and created female resource groups. A greater focus on the importance of work/life balance has promoted creative solutions and enhanced flexibility regarding childcare obligations for women and men.

Attitudes are changing and current hiring practices indicate that more people—men and women—are embracing a selection pool of qualified candidates.

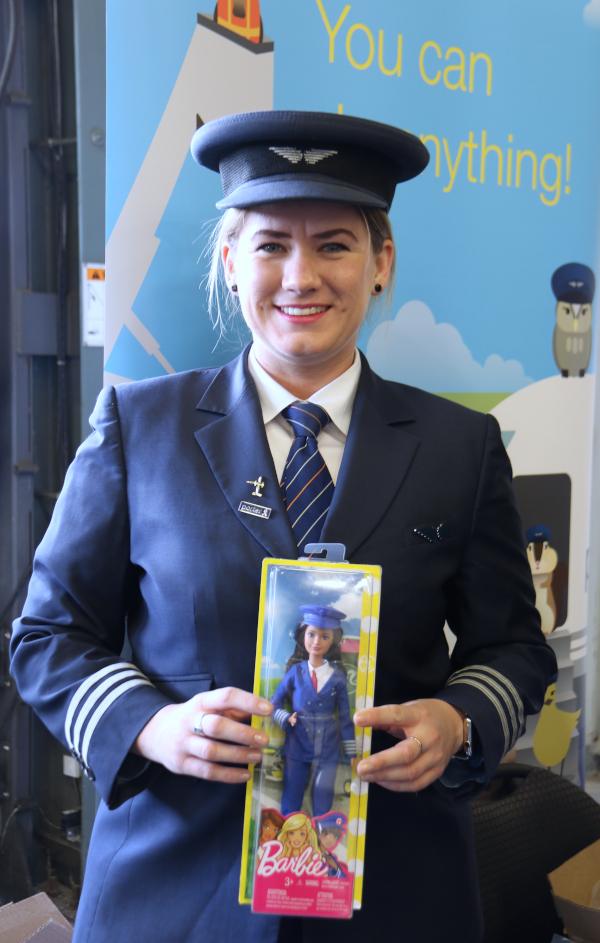

Socially entrenched assumptions that personality, ability, and performance are defined by gender must be revisited by parents, teachers, and caregivers. Although many traits are inherited, the modification of behaviour by experience and nurture (socialization) should not be underestimated. The elimination of gender bias has many obstacles, including resistance to change and the dearth of female role models in cartoons, the media, and toys.

An excerpt from Gender Equal Play in Early Learning and Childcare (2018), p5, details common traits perceived as genetically determined by nature (expectation).

Boys are expected to be strong, adventurous, rough, rational and leaders. Girls, on the contrary are sensitive, caring, submissive and illogical. Boys’ toys focus on action, construction, technology, fighting and conquering. Toys for girls focus on dolls, cooking, being a princesses, or art and craft. Men must be physically strong, aggression is an acceptable part of their behaviour. Females on the other hand should value being attractive, compliant, sweet and submissive.

The visibility of women in aviation can be increased by educational outreach programs and presentations by female pilots, avionics/radio technicians, aerospace engineers, and maintenance engineers to girls—and boys. For primary grades, a valuable resource is A Mighty Girl, marketed as “world’s largest collection of books, toys, and movies for parents, teachers, and others dedicated to raising smart, confident, and courageous girls.”

The WIAAB reports that “From 11–18, girls continue to be subjected to gender-limiting stereotypes and face bias and harassment for behaving outside of societal norms.” At this critical point in development, many girls begin to doubt their abilities and lose confidence in themselves. To counteract this trend, Ontario secondary schools mandate Careers Classes to introduce teen girls and boys to careers they may not have been aware of or considered.

Across Canada aviation programs such as Aviation Girls’ Club and the Department of National Defence Air Cadet program are offered. Open to youngsters 12-18, Canada’s Air Cadet program offers courses for aviation-related technical trades, aerospace technologies, and air crew survival. Some cadets will become licensed glider and/or fixed-wing private pilots.

Though students can begin flight lessons at any age, to fly solo in an aircraft, you must be age fourteen or older, be able to reach the controls, have a Student Pilot Permit issued by Transport Canada following a medical examination by a physician approved by Transport Canada, and—the green light from a licensed Transport Canada instructor.

To prepare for lessons, you’ll need the Flight Training Manual, a companion guide to the exercises in the pilot’s log book. This invaluable manual can be purchased at any time.

When you’ve completed forty hours of Private Pilot ground school (studying weather, navigation, aeronautical theory, and air regulations) and your copy of Sandy A.F. MacDonald’s benchmark reference manual, From the Ground Up, is battered and dog-eared, and you’ve acquired a minimum of forty-five hours of flight time—your instructor will prepare you for the Private Pilot Flight Test.

If you choose to continue training, you can get a multi-engine rating, an instrument rating (to fly through clouds), and/or a float plane endorsement. If you want a career in aviation, you can earn a commercial license when you have a minimum of two hundred hours of flight time, eighty hours ground school, achieve 60% on the written exam, and pass the flight test. At this point, you may start training to become a flight instructor. When you are age twenty-one or older, have fifteen-hundred-hours flight time, and achieve 70% on three written exams, you may qualify for an Airline Transport Pilot license. To learn the requirements for each license, consult Transport Canada Aviation Licensing.

Flight training is offered across Canada, at large airports with several paved runways, and at small airports with one, unpaved, dirt, gravel, or grass strip. All you need is an airplane, a landing surface, and a Transport Canada certified instructor. This course of study does not have any academic requirements other than being able to pass the practical flight test and the written exam.

However, a course of study at one of the many colleges or universities may require completion of STEM subjects at secondary school. As requirements differ between post-secondary educational institutions and programs, consult each institution and program to determine specific prerequisites.

In Ontario, several flight schools offer combined programs of flight training with a degree or diploma. For example, the Waterloo-Wellington Flight Centre offers a comprehensive program from first flight to Airline Transport Pilot and, depending on the student’s objectives, can be combined with a four-year degree from the University of Waterloo or a two-year diploma from Conestoga College. Other colleges such as Centennial, Confederation, Fanshawe, Sault, and Seneca offer a variety of aviation-related training programs for aircraft maintenance technicians, avionics (radio) technicians, or aviation management.

Alternatively, students may consider a military career beginning with studies Kingston’s Royal Military College.

Many women, at various stages during training and throughout their aviation career, credit their success to mentors and role models, and scholarships offered by international groups such as the Ninety-Nines International Organization of Women Pilots, Women in Aviation International, and CAE. Though the Ninety-Nines began with fewer than one hundred members, today the organization spans the world with more than sixty five hundred members in fifty eight countries. Two Canadian organizations, Elevate Aviation and the Northern Lights Aero Foundation, also offer scholarships and mentorship programs.

Inspired by the mantra, “You can’t be what you can’t see,” dedicated females from these groups host annual events at regional airports to introduce girls and young women to aviation careers, jobs they may not have considered possible—or even known they existed. The opportunity to speak with successful women enables girls to visualize themselves in similar roles. In Ontario, these events are Girls Take Flight hosted by the 99s at Oshawa Airport (April), Waterloo-Wellington Flight Centre’s Girls Can Fly (May), and Prince Edward Flying Club’s Find YOUR Wings (Sept), attended by flight schools, aviation colleges and universities, Air Cadets, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and Transport Canada.

With role models, dreams, and determination, success is possible. Silva McLeod grew up in a dirt floored, thatched roof home on the Pacific archipelago of Tonga, thirty five hundred km east of Australia. At age thirty seven, she became Royal Tongan Airline’s first female pilot. McLeod urges, “Never look to the top of the mountain because that’s when you’ll quit. It’s too high, too hard. But if you focus on the first step, chip away bit by bit, before you know it, you’re halfway up the mountain.”

1. Elsie MacGill was likely the first woman in the world to earn a Masters in aerospace engineering.