A life set in stone: in conversation with Victor Oriecuia. Aviva Jacob

How many people truly know, at just thirteen, what they’re meant to do in life? Perhaps at that age you wanted to be a doctor, a dancer, a fireman — something bold; useful; exciting. Preteens go through dreams like Kleenex: use once and toss aside. Whims are fleeting and superficial. At thirteen we’re just starting to picture our future: what might it be? What mark will we make on this world? Rarely, do we look back and see ourselves exactly where we thought we would be. Let’s be honest: what thirteen year old really knows what they want?

Well…Victor Oriecuia did. At thirteen he knew. He was going to be a sculptor. But this isn’t a story about a thirteen year old sculpting prodigy. It wasn’t until almost two decades later that Oriecuia tried his hand at the craft. For years he didn’t even pick up a tool, or touch a piece of marble. He didn’t have to. The desire, and more importantly, the skill for sculpting was innate. “I knew how to do it, even though I’d never held stone in my hands.”

In all that time — from thirteen to thirty — he did something much harder: he waited. Sitting down with Oriecuia, it doesn’t take long to note that he’s an extremely patient person, waiting until each question is finished; answering with carefully chosen words. That, he says, is something necessary for his craft. His whole life, and his work especially, are a practice in that very virtue.

Patience and Tools

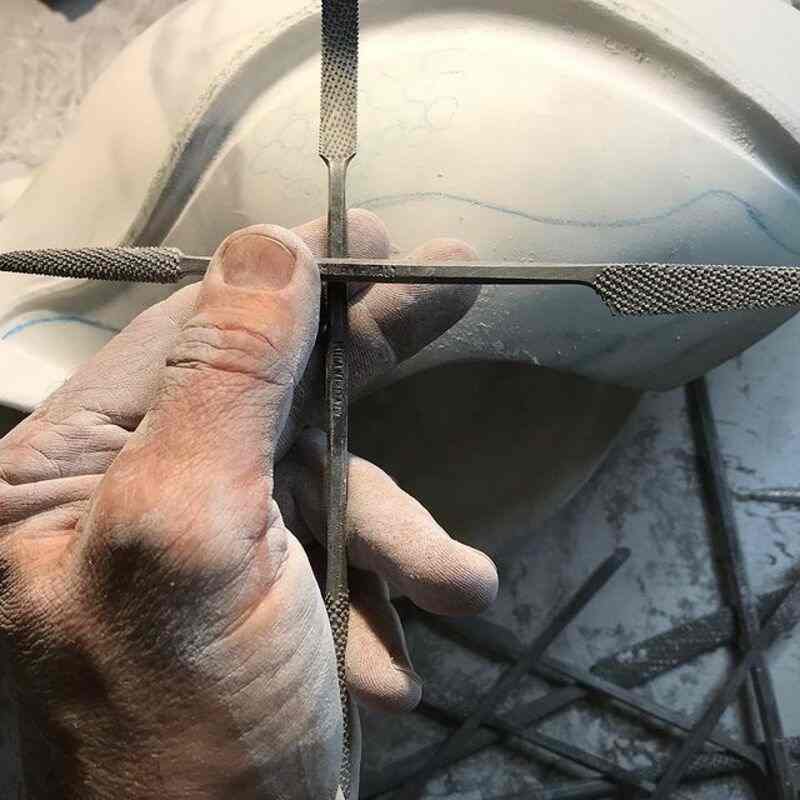

“Sculpting is ninety-nine per cent patience, one per cent tools.” Don’t discount that one per cent though. In making his plans to one day sculpt, Oriecuia slowly built an arsenal of tools. Each year he would purchase a new file, a chisel, a hammer. He would study them, hold them, feel their weight, learn their shape. Their importance can’t be overstated. Those tools are a conduit for the art; the bridge between sculptor and sculpture. They connect the man with the material.

Tools come from all over the world, from his hometown in Thunder Bay, Ontario, to the United States, through Europe — especially Italy. He describes his tool collecting as a pilgrimage of sorts. Many of the instruments he uses today come from the Milani Tool Depot, a small workshop in Italy where artisans make each tool by hand — crafted to fit into the hands of the masters. Artists seeking to use their tools have to travel to the small shop — at times by foot — in order to make the connection. Oriecuia, of course, has taken that trip.

“Pilgrimage” is an apt description of Oriecuia’s path. I might even argue that it’s the most important word in his story. I can’t talk about Victor Oriecuia — or his work — without talking about where he comes from and the journey he is taking.

Some people pay hundreds of dollars to learn their own history, spiting into a tube, and waiting for the results to arrive.

But, just like his knowledge that he would one day sculpt, Oriecuia always knew who he was. And instead of sending away for a genetic testing kit, he hopped on a plane to make his own connections to his past.

Pilgrimage and Purpose

Oriecuia lives in Kingston, and grew up in Thunder Bay, though his lineage originates in the foothills of the Alps, bordering Italy and Slovenia. His mother comes from Clavora; his father, from Ossiach. According to Oriecuia, it is a unique area where the Slovenian dialect which provides his unusual name, is spoken.

Steeped in tradition, families dating back centuries pass knowledge down through generations: food, drinks: wine and grappa, language, and — of course — art. That’s one of the biggest differences between Canadian and European society, says Oriecuia.

“We don’t have the Vatican. We don’t have the Louvre. There’s a tradition of stonework, an old world approach that we just don’t have here.”

That is something he wants to change. But how does one bring ancient knowledge into a new world?

“I want to change the perception […] and presentation of marble works. Stone sculpture can be warm, inviting, and recklessly fragile.”

In the nineties he spent a year with family in Italy, immersing himself in their culture and traditions. Talking about his time on the mountain he reminisces about the food — handmade sausages and cheese, the drink, genuine Prosecco and Italian wines. But above all else he vividly remembers the art.

Being based in the Natisone Valley, allowed trips through Italy and the rest of Europe. Still years away from practicing his craft, this is where the self-taught sculptor says he really began to see the impact of the medium.

“Milan, Spain, Greece, Switzerland. From Palermo to Rome, there are whole cities built in stone. If you live there it’s in your face daily, but for me, it was an awakening.”

Imagine yourself standing in a garden full of sculpture; a cemetery where marble monuments stand in the place of headstones; the work of the masters living outside the confines of museum walls. This, is an image he can’t forget; one that will live in his mind for the rest of his life, influencing each stroke of his file against stone.

Permanence is a word that comes to mind when he thinks about this part of the world and the art that has been created there. Sculpture has everything to do with the past and the present meeting each other. Even the stone itself holds a deep connection to the earth — its ancient, geological lineage.

Carrara marble, for example, is unique to the place it’s named for — Carrara, Italy. Used for centuries, carted around the world and built into structures still standing today.

“Each quarry or each mountain range will have its own variety of marble. It all depends on what was originally in that sediment base. Depending on time, pressure, whatever organisms actually inhabited that area, can result in a different marble type or stone type. Each stone is different — while also being directly related to the stone that came before it.”

Stone and Craft

Oriecuia’s first stone was white marble which came into his life at the exact right moment in 2004 — seventeen years after he started his pilgrimage towards sculpting — the moment he was finally ready to begin.

To this day he collects his materials from around the world, visits quarries, picks stones by hand, seeking history, as well as quality.

Carrara marble, might have the most recognizable name, but it’s far from the only stone with a past. He describes a piece of Belgian black marble that he purchased in 2014: a type of stone that can be traced back to 15th century architecture.

“That marble is actually part of the Taj Mahal. It’s inlaid into the building. It’s also the same marble used in the Vatican. That’s part of what I’m looking for: stone that I can connect to physically, mentally, emotionally, historically, spiritually.”

His collection now stands as a sort of living world map — each stone a marker for its birthplace. He uses everything from Kingston limestone, to Vermont marble, to those very ancient stones originating in Europe.

And just as they each have a unique origin, Oriecuia says every piece of stone has its own behaviour — its lineage dictating how it must be manipulated in the sculpting process. Violent, blunt movements can give way to softer, fluid strokes, depending on the stone. Tools become important. Beginning a sculpture may require harder strikes of the hammer, but as it whittles down into its intended shape, chisels and diamond files get smaller and smaller; movements become more delicate. “I’m holding my breath, removing single crystals at a time.”

“Whatever the stone says it needs,” — that’s Oriecuia’s mantra. And he relies on all five senses to determine that need. In choosing his stone he’s looking for quality in the shape of the veins, the colours deep within, the way light hits the material. Early on in the carving process he feels the grain of the stone between his fingers; smells it, even tastes it, familiarizing himself with the object as it is. As he works he listens for changes in tone as his instruments move through the stone — each subtle change determining his next moves. He follows its lead.

The job of the sculptor is to reveal what’s hidden inside each piece of stone. His art is one of contradiction. He creates by removing; builds by taking away. Stone is strong yet fragile; ubiquitous yet unique; it is — as he puts it — “both soft and dangerous.”

Sacro Fiore: Sacred Flower

His latest body of work — a collection now years in the making — uses flowers as the central subject. It’s a perfect embodiment of the contradictions of stonework; the delicate form carved out of solid material; movement depicted in the immovable.

He calls the collection Sacro Fiore, meaning simply: Sacred Flower, in Italian.

One piece, Puppet Flower, is carved into that ancient Belgian black marble, with a centre formed from twenty-three carat gold leaf. It sits atop a solid stone pedestal — strong, yet delicate.

The piece derives its title from the Leonard Cohen song, Puppets, a short but powerful tribute to the lives lost during the Holocaust and World War II. Taking the form of a Poppy dripping down a pedestal, it is inspired by the history of the war. Its base is pockmarked with holes resembling wounds left by bullets. Inspired by a visit to the Ponte Vecchio Bridge in Del Grappa, Italy, which stands as a living monument to the damage done in the war; evidence of the gunfire remains untouched…immortalized in the landscape.

The piece is meant to represent loss, heartbreak, and damage. At the same time, it’s full of strength, and maybe a little danger.

“The fine points of the flower, at the edges of the petals, are so fine you could cut yourself.”

There’s a simple reason for his recent choice of subject: flowers are a universal language. For centuries, they’ve been used to celebrate life, commemorate death, convey love, loss, joy, and sorrow. Their meaning and importance can transcend words.

It’s a fitting metaphor for the artist himself. Looking at his work I find myself without the words to express what’s in front of me. The objects he’s created contain so much history — that of the stone, the tools, and the artist.

Sitting in front of his work, I’m reminded of, or perhaps haunted by, a word used often in our conversations: master. In recounting his path to becoming a sculptor he speaks of the masters of the craft: Michelangelo, Bernini, Canova.

But it’s deeper than that, he proposes. “A master does not have to be famous.” I have to ask then: what does make a master?

This is a question he doesn’t fully answer. Perhaps he doesn’t need to.

Though humble, he clearly knows his value. He continues to study every day; increasing his physical skills, building his knowledge of anatomy and the human form.

He works through the nights, sometimes forgoing sleep, to balance his role as a father and husband, with that of sculptor.

He travels when he can, investing in stone and tools, working alongside his contemporaries, sculpting while standing on the same earth as some of the masters who came before him.

He says he’s getting better all the time. It took Oriecuia nearly two decades to put his hands on stone. Now, he’s spent another two immersed in the practice.

And really, he’s only just getting started.