An organized society, or ‘polity,’ is made up of innumerable interactions among individual persons – and between each of us and the myriad of laws, norms, policies, and practices that govern the ways we navigate our way through daily life. Never mind the overrated internet; the real ‘world-wide web’ is the profuse, intricate network of connections between people, regulatory bodies, and commercial enterprises – among other entities, like religious, cultural, educational, recreational, and volunteer-driven community service organizations. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle said “Man is by nature a political animal” – or, more literally, “an animal which lives in cities.” For Aristotle, the ideal polity is one in which we respect each other’s rights, live by mutually agreed rules, and are governed with our consent. In a very real sense, the polity is us, and we should be ever mindful of ways to make it more just, more amenable to the attainment of the full potential of each of its members, and more conducive to their general welfare. Perfecting a polity is a perpetual work in progress. And, we still have a lot of work to do. Consider these examples from the realms of representative government; constitutional reform, individual freedoms, the regulation of commerce; strengthening consumer protection, repairing a broken legal system, practicing a foreign policy that truly reflects our shared values, and addressing cultural conundrums like those governing our approach to minority communities.

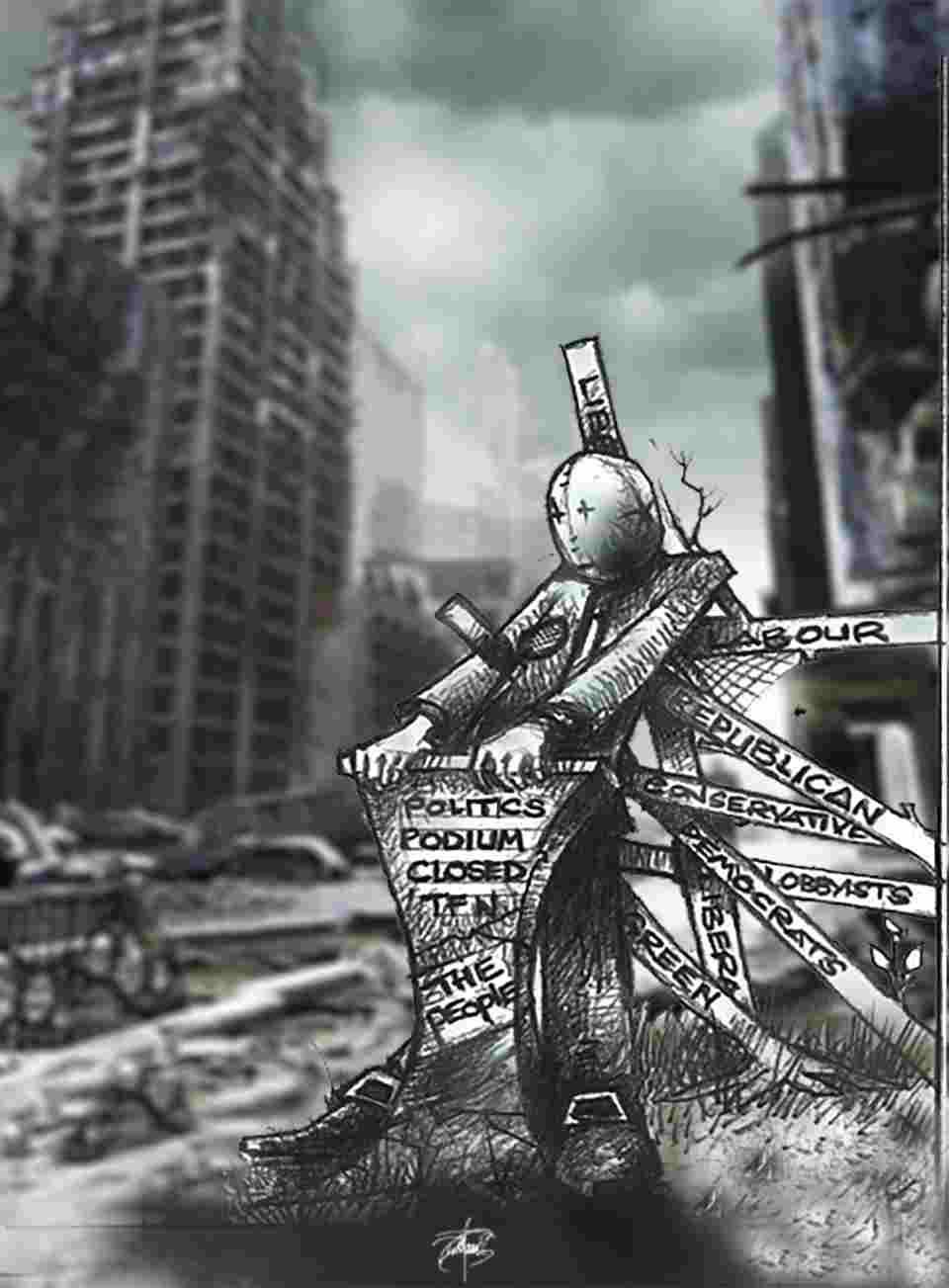

Charles de Gaulle observed that, “Politics are too serious a matter to be left to the politicians.” His contemporary, the French poet and man of letters Paul Valéry, observed that, “Politics is the art of preventing people from taking part in affairs which properly concern them.” In Canada, we have periodic elections, of course; but most of us have very little ability to influence public policy. Those elected to represent us may not heed, let alone implement, their constituents’ views. And, after many years of power being unduly concentrated in the hands of the Prime Minister and his close staff, even individual Members of Parliament have very little say in the decisions that affect all of us. There are ways to ameliorate those problems. We should impose term limits to ensure that fresh faces are constantly re-oxygenating the electoral waters and to forestall familiar ones from making a perpetual perch out of public office. We should enact recall provisions which empower the electorate to compel a by-election when a threshold number of voters sign a petition expressing ‘no confidence’ in an elected representative.

We should severely circumscribe a Prime Minister’s unilateral power to ‘prorogue’ Parliament. In December 2008, Stephen Harper used that power to derail an effort by opposition parties to replace his Conservatives with a coalition government. More recently, in August 2020, Justin Trudeau used it to blunt the critique of his government’s ethical failings in the ‘We Charity’ scandal.

We can put meaningful power into the hands of individual members of the federal and provincial legislatures by empowering party caucuses to overrule party leaders by majority vote and/or by mandating that most votes in Parliament be free from party control. Both of those measures should be entrenched in the Constitution to ensure compliance. We should experiment with proportional representation, both federally and provincially. The existing ‘first-past-the-post’ system means that a party that gets a plurality of the votes (i.e. more votes than any single competing party but not the overall majority of the votes) can, and often does, get a majority of the seats in the legislature. It’s a result that does not fairly reflect the way the electorate actually voted.

And, while we’re on the subject of experiments in representative government, let’s try something truly outside of the box with a trial-run at selecting representatives by random draw, precisely as now happens for the serious responsibility of jury duty, in lieu of conventional elections. Although voters would lose the chance to size-up prospective candidates, each and every one of us would instead become a latent legislator – potentially being called upon to do our civic duty by representing our fellows at city hall, in a provincial legislature, or at the federal Parliament. Wouldn’t it make us more invested in our own governance – and less cynical about political affairs? A simple screening measure (to ensure sound mind and good character) could adequately weed-out those who are unfit. Those selected would have their preexisting jobs held for them while they were assigned the temporary role of ‘Citizen-Legislator.’ We’d have a random sampling of people from all walks of life. And, with one fell swoop, we’d rid ourselves of the unwelcome specter of professional politicians, whose quest for election prompts them to (often disingenuously) tell us what we want to hear while they put their own interest in reelection over the public interest and too often vilify those of opposing affiliation in the process.

Matters concerned with the nation’s public institutions lead us into the always problematic waters of constitutional reform. Any self-respecting wish-list for those core reforms would include the following: Canada’s unelected Senate should be abolished and replaced with one that is equal, elected, and effective: it would have substantive powers and its own areas of special responsibility; and it would be comprised of an equal number of Senators – either from each province or from each designated ‘region’ of the country. We should consider abolishing the mostly ceremonial positions of Governor General and provincial Lieutenant-Governors and instead have our ‘Heads of Government’ (the Prime Minister and provincial Premiers) assume ‘Head of State’ responsibilities in their stead when the constitutional monarch is not present in person. Also, at present, municipalities exist entirely at the whim of provincial governments; instead, they should be entrenched in the constitution as a separate level of government.

The Constitution should also belatedly implement a common market in goods and services within Canada: it is a travesty that Canada has existed for 153 years without that basic feature of nationhood. A reformed Senate should be given special responsibility for protecting the nation’s two founding languages – in effort to shift the protection of the French language from the selfishly parochial grasp of the province of Quebec. We should remove the Prime Minister’s sole control over appointment of Canadian Supreme Court justices; instead, a panel of experts could recommend potential candidates for those positions for consideration by Parliament. Unless and until mandatory retirement at age 65 for others is abolished, Supreme Court justices should be held to the same restriction – instead of their current retirement age of 75; there is no good reason to give them preferential treatment. We need to reconsider the Constitution’s sometimes archaic division of federal/provincial areas of jurisdiction. National standards in areas like health care and in the recognition of professional qualifications (for doctors, lawyers, nurses, teachers, and others) are long overdue. In the area of individual freedoms, we need much stronger privacy protection for all Canadians from state and corporate intrusion.

And what about requiring binding referenda to put questions of conscience or universal impact directly to the electorate? Hearkening back to a long-past issue by way of example, Canada’s switch to the metric system (which began in 1970) should have been left to its citizens to decide by direct vote. Controversial matters like abortion, euthanasia, same-sex marriage, and the legalization of certain narcotics might be suitable candidates for referenda, too, insofar as the issues involved may be too ‘big’ and too connected to personal values for mere representatives to resolve on their own.

The way we regulate (or, too often, fail to regulate) commerce has profound implications for all members of the polity. We urgently need much stronger competition law; the never-ending concentration of money and power in ever fewer hands is anathema to meaningful competition in our supposedly ‘free market’ economy – a result that daily cheats consumers. We need much higher tax rates (approaching 100%) for extreme wealth. We need a definitive end to the practice of hiding income in foreign tax havens. We should require worker representation on boards of directors. Employees’ salaries and pensions should get coequal priority in the law with secured creditors in cases of corporate bankruptcy. And, why not impose a fixed limit (say, five percentage points) on the differential between the interest rate paid to depositors by banks and the interest rate said banks can charge for credit card purchases and certain other debts? Throughout much of 2020, for example, financial institutions paid a mere fraction of 1% per annum in interest to their hapless depositors while inflicting usurious interest rates (in the vicinity of 20% or more per annum for credit card debts) on the self-same customers: they should be forbidden by law from doing so anymore. Under the proposed reform, if a bank pays you a paltry 0.2% in interest, at least they would be barred from charging you any more than 5.2% in interest for credit card debt, personal loans, or residential mortgages on one’s actual dwelling-place.

Regulations governing consumer protection in this country are woefully lax. We need strong new measures to curb the notoriously excessive pricing of things like banking machine (ATM) use, cell-phone contracts, bank fees, cable TV, internet, and auto insurance. ‘Market forces’ on their own are failing to ensure competition and reasonable charges. We should require 51% membership by laymen on professional disciplinary committees (e.g. judges, lawyers, doctors, dentists, accountants, et al.), so we don’t have bad behaviours inadequately regulated by self-interested practitioners in the same field. We should impose scrutiny and accountability on professional self-regulatory bodies. For example, the Law Society of Ontario, which regulates the 50,000 lawyers in this province, is needlessly (gratuitously, even) opaque, undemocratic, and utterly unaccountable – to the detriment of its members and the public alike.

The neglect of the elderly in this country is not just scandalous; it is a crime, quite literally. An October 2020 investigation on CBC-TV’s “Marketplace” revealed that provincial investigators reported 30,000 violations in Ontario’s long-term care homes over the past five years. Worse still, those official violation notices resulted in no consequences – none. 538 long-term care homes broke mandatory rules repeatedly – with no sanctions, no fines, and no criminal prosecutions – even for instances of flagrant neglect or outright abuse of the elderly. Ontario’s Minister of Long-Term Care, Merrilee Fullerton, recently had the gall to say that, “There’s no tolerance whatsoever for negligence or abuse” – a preposterous contention that is flatly contradicted by the fact that not a single criminal charge has been filed against the perpetrators of such crimes. Indeed, 85% of Ontario’s nursing homes have repeatedly broken the law for abuse and neglect – and gotten away with it time and again. We need iron-clad national standards governing nursing homes; an end to profit-driven nursing homes; zero-tolerance for abuse and neglect; criminal charges for those who commit such offenses; and closure of nursing homes for the most serious offenses. While we’re at it, we should ensure that said national standards abolish shared rooms and require air conditioning: most of our seniors have been stewing in extremely hot rooms during our severe summer weather. We need also need better trained staff, who are screened for empathy as well as competence, and a far more sensible staff-to-patient ratio.

Our system of justice is premised upon the fiction that people can pursue their rights through the courts. But most people cannot begin to afford to retain a lawyer for litigation cases. Consequently, too many people are obliged to abandon their rights altogether or to struggle to represent themselves. That renders our system of justice a dysfunctional failure. We must urgently seek ways of addressing this unacceptable situation. One approach might be to substantially increase the funding and the coverage of provincial legal aid programs. Another might to be to consider mandatory ceilings on the hourly fees charged by lawyers. Without action of some sort, there will continue to be no access to justice for most Canadians.

What are some of the other aspects of a broken legal system? For one, recidivists are routinely re-released on bail pending trial by jaded judges and prosecutors – in flagrant contravention of provisions intended to protect the public. We should consider reducing the discretion available in enforcing such provisions. The number of “bad apple” judges, who behave abysmally in the courtroom, would shock a casual observer. The so-called preventative measures in place are laughably feeble; new measures are needed to enforce proper judicial decorum and thus halt erosion of respect for the administration of justice. A novel approach might be incognito ‘inspectors-general’ with the power to act decisively in the face of misconduct by suspending a judge on-the-spot pending the disposition of disciplinary charges.

Some issues involve not only questions of core cultural, historical, and legal principles but also personal convictions – even as they go to the heart of what kind of country we want Canada to be. For instance, should we abolish state-supported multiculturalism in favour of encouraging newcomers to assimilate? And, should we consider an even bigger sea-change with respect with indigenous peoples, by, for example, phasing out all state-sponsored reservations? It would be no easy matter (to put it mildly) to enact substantive change in that area, entrenched as present arrangements are in our Constitution, binding treaties, and the decisions of upper courts. But, there’s a conundrum or two at the heart of things: In the first place, how does it make sense in 2020 to call some Canadians “Indigenous peoples?” In what way are they “Indigenous,” any more than the rest of us are “colonists” or “settlers?” Some of us are descended from colonists, settlers, or immigrants; others of us are descended from Indigenous peoples. More problematic still, with the unfortunate exception of a figurehead hereditary monarch, we do not inherit rights or status based on whom we are descended from. However much ‘aboriginal rights’ and ‘Indigenous status’ are currently entrenched in our laws, the very act of entrenching them, on the otherwise suspect basis of inheritance, contradicts our core principles of equality before the law and universal rights as the common legacy of all people.

Public morality is out of favour these days as a topic of discussion, but it is at the heart of other issues that affect the polity. Does advertising for gambling (lotteries, casinos, etc) belong in print, broadcast, or online media? Is the normalization of gambling in the public interest? The same goes for the legalization of some narcotics. Is normalizing recreational drug use in the best interest of society? Opinions on those subjects will vary enormously, and they will inevitably be influenced by private convictions and personal tastes; but they’re worth fearless consideration by those interested in the public good.

Finally, we need to practice a foreign policy that truly reflects and upholds our core values. Instead of simply “raising concerns” about human rights abuses at high-level meetings about other matters, we ought to do something about them. We should actively oppose having prestigious international events like the Olympics held in countries, like China, which are shameless abusers of human rights. Likewise, we should oppose having the next G-20 heads of government meeting held in Saudi Arabia, a tyranny, like China, which unapologetically attacks human rights and hurts people. If we are overruled and such meetings in such retrograde places proceed over our principled objections, we should boycott those meetings and encourage our democratic allies to do the same. That’s called putting our principles into action.

It may surprise many people, here and abroad, to learn that Canada is a substantial exporter of arms. We like to regard ourselves as a mostly peaceable kingdom. Yet, in June 2016, “The Globe and Mail” reported that Canada was the second biggest arms dealer to the Middle East. The lion’s share of our arms sales to that volatile part of the world consisted of a large shipment of combat vehicles to Saudi Arabia, which may be using them in the protracted, ruinous conflict in neighbouring Yemen. In that same year, remarkably, Canada was ranked as the sixth biggest arms exporter in the world! What is the moral polity to do? The answer is crystal clear: we must permanently restrict our sales of military weapons and equipment to fellow Western democracies which respect human rights (lately, that would exclude our ostensible NATO ally Turkey) and insist on guarantees that said recipients will not in turn resell Canadian arms or equipment to any other nation.

As a party to the ‘United Nations Convention against Torture,’ Canada is “obligated to prohibit, prevent, and punish acts of torture [and] to provide redress to survivors in Canada.” But, as the Canadian Center for International Justice puts it, “it is not enough to merely denounce torture. Canada must also hold perpetrators accountable and provide legal avenues to survivors in Canada seeking reparations.” An obvious mechanism for accomplishing those objectives is to permit injured parties in Canada to sue foreign governments and their agents for harm inflicted abroad. Perversely, though, our ‘State Immunity Act’ still shields governments accused of torture and other forms of ‘cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment’ by giving them immunity in Canadian courts from civil lawsuits seeking redress for such crimes. There is ample precedent in Canada for us to amend that law and further restrict the application of state immunity. Around 1980, a Canadian citizen claimed damages against the Soviet Union for unpaid printing bills and attempted to have a sheriff seize a Soviet merchant ship in Toronto’s harbour in execution of a default civil judgment. The ensuing severe diplomatic incident (the Stanislavsky matter) focused minds at the Department of External Affairs on the subject of state immunity. Canada subsequently acted to replace its existing “absolute immunity” regime with a “restrictive immunity” regime, which stipulated that foreign states would no longer be immune from the jurisdiction of Canadian courts if they engaged in commercial transactions here. As one of the drafters of the new limited immunity approach, we have to ask – why should foreign states be answerable in Canada for commercial disputes but not for the heinous crime of torture? The answer is that foreign states ought to be held accountable for the crime of torture, and Canada’s State Immunity Act should be further amended to facilitate said accountability. That’s another way of practicing a foreign policy that truly reflects and upholds our core values.

The polity is us: let’s work ceaselessly to make it a better one.