Gary Michael Dault, CM Before and After

“It’s not what the artist does that counts, but what he is.” Picasso

Both Monet and Picasso considered Cezanne an artist’s artist. Monet collected Cezanne’s work whereas Picasso was inspired to purchase a piece of land that provided Cezanne with his famous motif, Mont Sainte-Victoire. Each of us has an artist or two, or a few, who inspire. I’ve known Gary Michael Dault for years, through his work in the Toronto art scene and more recently when I curated an exhibition of his paintings in 2018 at the Arts & Heritage Centre in Warkworth Ontario. I am lucky to own a couple of his small pieces, not inspirational accounts of the south of France but rather, two small landscapes, one from about twenty years ago depicting a Toronto residential scene inscribed with text and the other, more recent, of what appears to be a writer’s desk and window viewing an oceanic (Freudian) landscape. Both pieces, (not shown here), are important works in what they do for me. They are of the artist, as artefacts of cumulated knowledge projected onto a surface in paint and ink. I have something of the artist to think about and dwell with. In my home and studio, I live with the work and consider his life of thinking, making and being. Words insufficiently describe the visual world. How does one use text to explain the condensed expression of visual poetry or poetry using actual words for that matter, at which Gary Michael Dault is also very good. I don’t know whether he would wish to be called an artist’s artist; perhaps the mere fact that I think it makes it true, altering Descartes’ maxim, ‘I think therefore he is’.

Gary Michael Dault “contains multitudes” as Walt Whitman wrote about himself in his epic poem ‘Song of Myself.’ Nobel laureate Bob Dylan recently stole from the 19th century poet for one of his own songs. While living in Toronto, GMD wrote prolifically for the Globe and Mail on the visual arts and on contemporary artists at work in a lively urban art scene. Writing on the work of one who writes about the work of others is timely because we should consider the contemporary condition of categorization, colonial or institutional. It’s finally time to celebrate the contemporary artist who embraces multitudes. GMD is the polymath, a lettered, conversant, studied artist.

Late last year, I spent an afternoon interviewing Gary in his Napanee home for the Youtube series on artists presented by the Art Gallery of Northumberland*, while welcomed and feted by his lovely wife Małgorzata Wolak Dault, with whom he occasionally collaborates. Before and after the camera rolled, we talked about the multiple lives of GMD – a man who also happens to be fond of cats. Like them, the artist has many lives, fewer than nine perhaps, but all linked through a continuous thread. Now in his early eighties, he is primarily focussed on painting and the written word, poetry. His words, like the paintings, are packed with allusions, references, juxtapositions; always efficiently composed and deceptively minimal. The paintings these days are often small, the world(s) he paints, however, astonishingly epic. The poems are alluring, typically concise, and apt.

Adjacent Flowers

newly

adjacent

flowers

your eye springing

on their

trampoline petals

their colour

swarms you

like sudden

tawny animals

in a forest

Artwork is that which remains of the artist. The daily struggle, the quotidian, are merely footnotes. Gary Michael Dault understands the importance of the moment in art practice, especially in late life. His current work, like the works of senior artists of the past, is efficient, to the point, rich in colour relationships, nuance, composition, line, and lyrical movement. To notice, to look, to listen and observe is action. It’s ninety percent of what the artist does and to draw, make, perform is to simply mark in time what he sees and knows. How hard is it to do well? Very.

In GMD’s Notebooks Series, the small painting ‘Still Life in the Time of War’ 2022, contains a quiet power which neither threatening tanks nor incredulous propaganda can refute. In the most lucid and circumspect way, this work stands for resistance. The still life is a domestic arrangement, a place/space we all know. Each of us designs our home to contain essential beauty: the vase, the flower, the studied objet d’art. Imagine our dwelling under attack, under siege. Does it, do we, cave in, disappear, or stand still, irreverent to the force of evil and thoughtlessness? This vulnerable painting represents quiet universal defiance. It is a figurative piece, fragile but forever strong in spirit. A still-life painting like this is beautiful because it embodies us in the face of Thanatos or more precisely Eros and Thanatos, guiding the way.

A Pale Blue Teapot

a pale blue teapot

breathing like a lung

still feels the silver hand

of its maker

stroking its memory

still fixing its convexities

in place

for the vessel’s ride

through the seas of performance

a teapot like this

is a grail of completion

when empty

it is at a voluminous standstill

nothing can tip it

into time again

In the small painting called ‘Yellow Teapot’ we see a vessel floating in a sea of Mediterranean blue, a specific hue perhaps subliminally evoking the artist’s paternal roots. Simultaneously, the vessel metaphorically contains both body and mind; it is the essence of an architecture separating and joining interior and exterior realities. A vessel carries stories and is a prime metaphor for relational architecture, between the self and the exterior world, humans separated from nature. Vessels of this kind are a frequent motif in GMD’s notebooks and paintings. The capacity of the vessel as a theoretical category and physical analogy has a long cultural history. We see GMD’s dense allusions to ancient Hellenic funerary vases and ships, biological vessels containing the cells of life and collective and individual vessels containing subconscious. GMD’s representations of teapots and other vessel forms reach back to our collective past.

Gary Michael Dault posts work weekly, images and words, on Monday Art Post published by Lee Ka-sing and Holly Lee.* Speaking of cats, one Art Post depicts Gary and Malgorzatta’s representations of their treasured cats with fifty-three images (not cats) in total and accompanying text. As anyone who adores cats well knows, the daily interaction with feline culture is an alteration in balance of power. In this case, drawing cats is a function of reflecting. I think of Plato’s Parable of the Cave when viewing Gary’s cat paintings – which happen to look a bit like cat shadow puppets – who is the puppeteer in the home cave, the cat or human? We can’t be certain. We all live in some-kind of ‘prison’, out of necessity perhaps, but just as Piranesi depicted in his celebrated 18th century etchings Carceri d’invenzione, an imaginary prison can be quite a comfortable place to dwell.

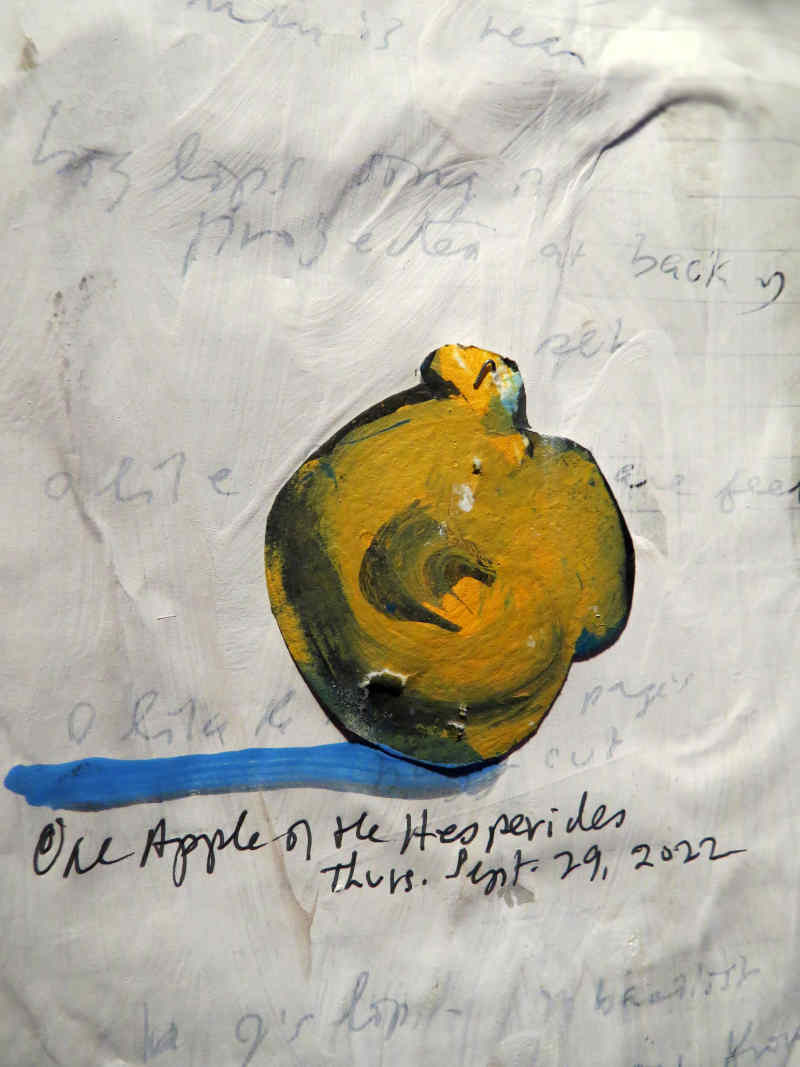

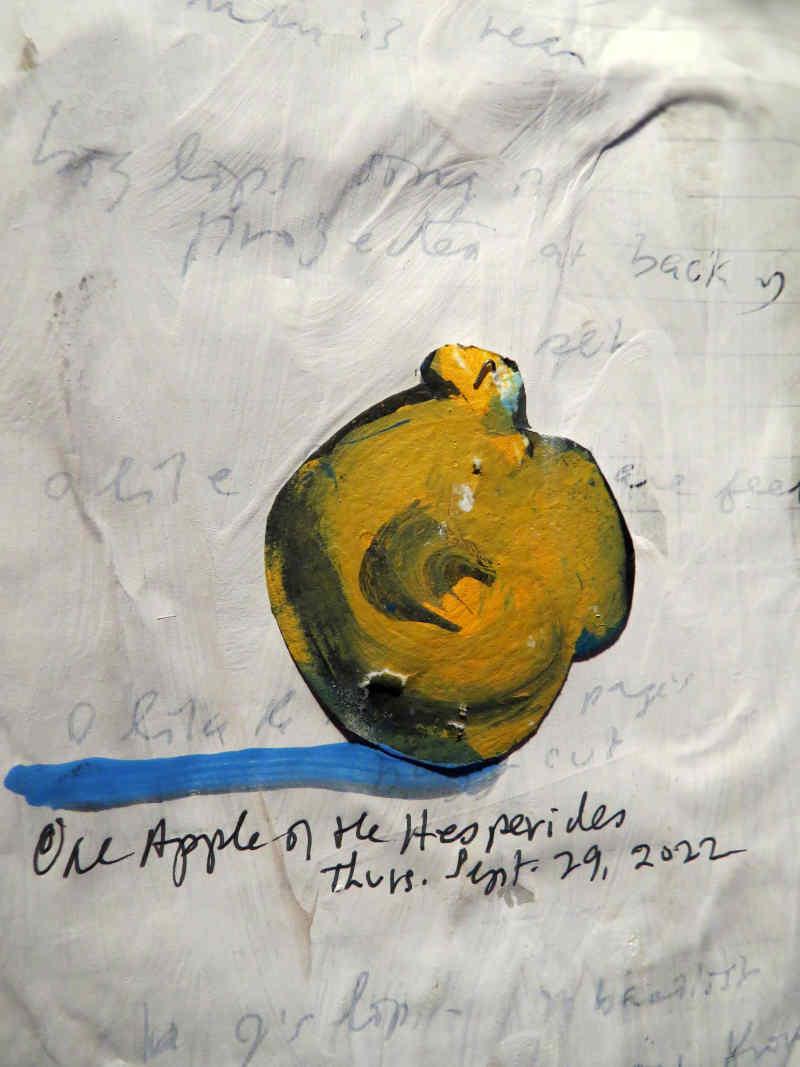

The still-life painting One Apple of the Hesperides is a representation of Nature’s solitude. The Apple starts in Ellas, appearing and disappearing through the centuries, reaching all the way to early French cubism and then landing on Gary’s table. The apple now is re-rendered as a glitchy platonic form, reduced by a few strokes of paint on paper, cardboard, or canvas. He invokes a layered palimpsest, image and word combined, story upon story re-told. In Greek mythology, the Hesperides were maidens beyond the ocean who guarded the tree bearing golden apples belonging to Hera from her marriage to Zeus. The Hesperides maintained a magical garden situated at the edge of the world somewhere in the west, beyond civilization. The apple represents Gift, a glimpse of sunset, toward the native garden (lost nature) beyond the knowable world. In one of Heracles’ many labours, he travelled to find and return the Apple of the Hesperides. When Heracles came home with the treasure, he gave it to his brother Eurystheus who, concerned about owning something stolen from the gods, then gave it to Athena who returned the treasure to the garden. Just as well, for this may be a non-reason we can still enjoy Nature’s sunset. And in this diminutive yellow-sunset coloured apple, Gary Michael Dault takes us to the Before, the Garden, in anticipation of the After. In the artist’s own labour to repatriate or re-connect with the collective past, we witnessed a lonely journey through an individual pursuit (of art) in a way that floats above daily life, the finite day.

Gary Michael Dault was appointed to the Order of Canada in 2018 for his “contributions to Canadian arts writing and for his commitment to celebrating visual artists.” As a student in Toronto, he studied with literary giants, Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan, amongst others. He has taught at multiple institutions and university departments, including time with architecture students at the University of Waterloo and the University of Toronto. In conversation, at eighty-two, he is sharp as a knife, funny, and does not suffer fools. He loves a good joke and is as swift in word exchange as he is with the brush. He leads mostly but entertains a willing dancer. His footwork dazzles, and his tongue is always precise and erudite.

Dimitri Papatheodorou

* Monday Art Post: https://artpost-cats.blogspot.com/

Gary Michael Dault, “Still Life in Time of War”, Nov.17, 2022, notebook image

Gary Michael Dault, “Yellow Teapot”, from A Book of Vessels, published 2022 by Ocean & Pounds, Lee Ka-sing and Holly Lee, publishers of the Monday Artpost.

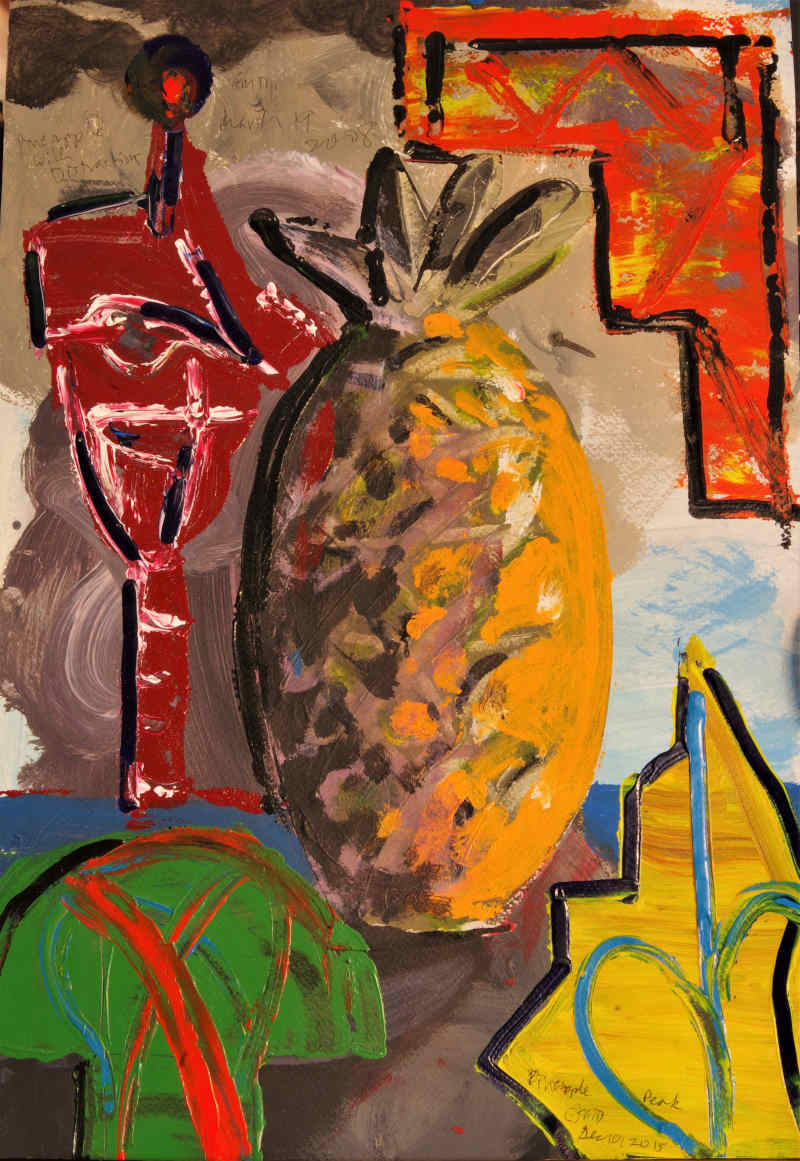

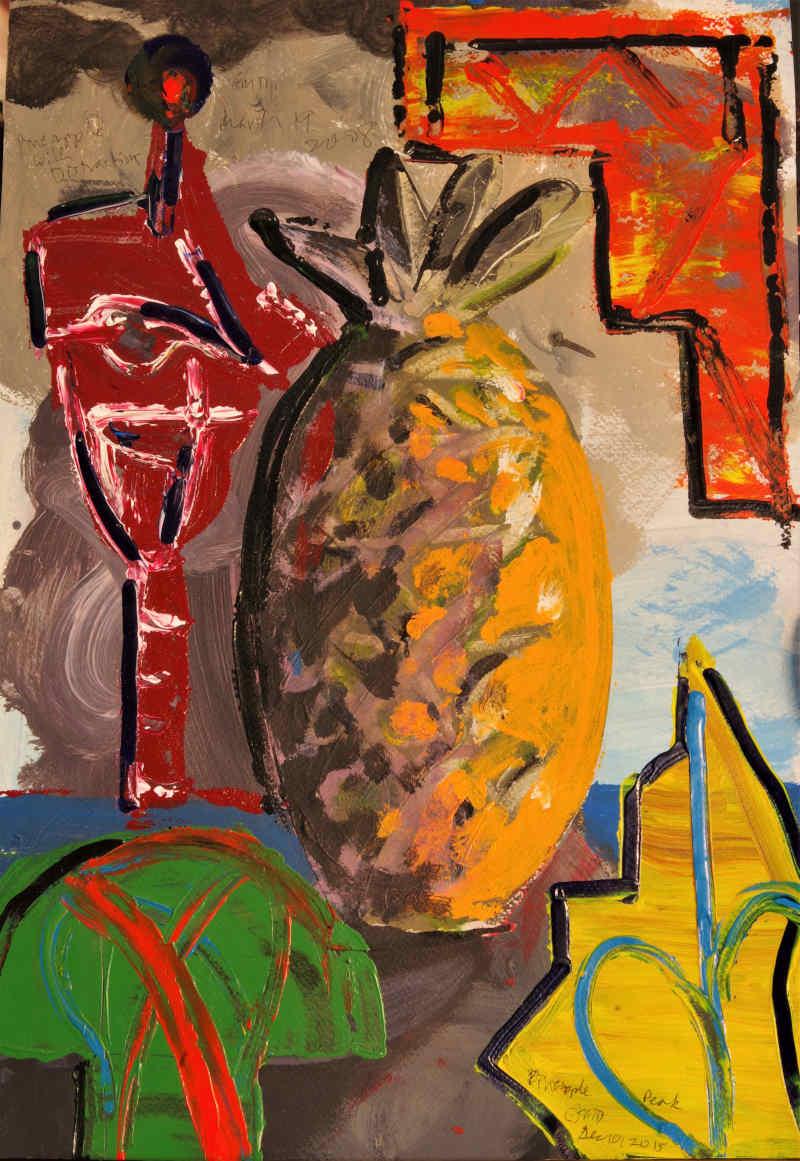

Gary Michael Dault, “Pineapple Peak”, December 10, 2015

Gary Michael Dault, “One Apple of the Hesperides”, September 29, 2022

Gary Michael Dault, “Electric Car”, Oct.16, 2022

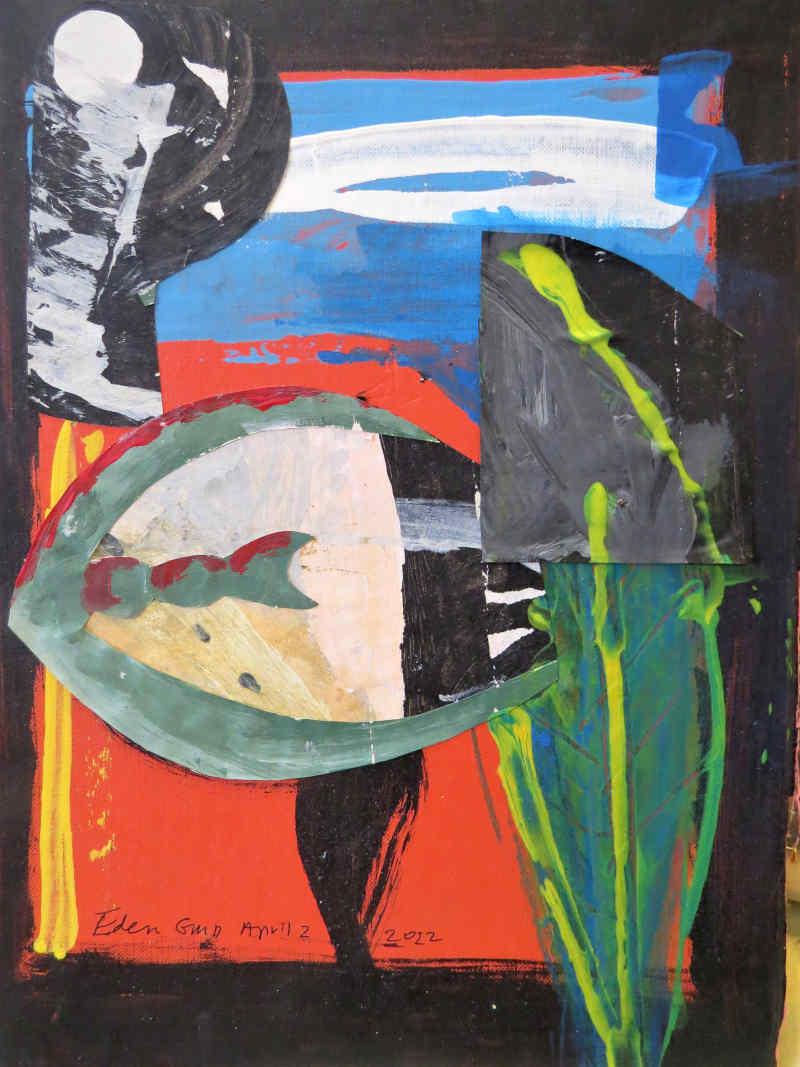

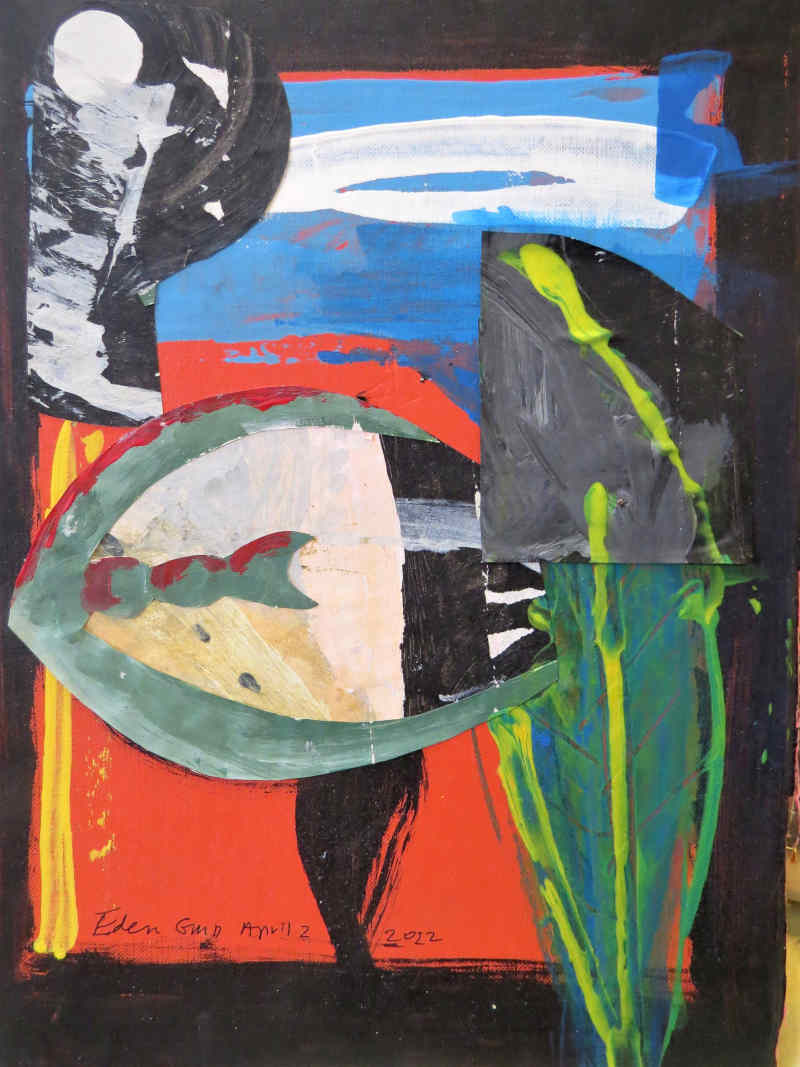

Gary Michael Dault, “Eden”, April 2, 2022