It was way back in 1970 that I finally became sufficiently

consumed by the passions of contemporary art to walk out of

graduate school and start driving a cab. I was going to paint

and write and pilot my cinema noir taxi through the mean

streets of Toronto and be a tough-guy artist.

When, inevitably, cab-driving began to lose its charm, I

swaggered into the Ontario College of Art and fast-talked my way into a small, once-a-week teaching job. It was an open seminar I decided to call “Ideas for Artists,” and it happened every Wednesday Morning.

That was where I met Steve Armstrong. He was one of

the seminar’s brightest luminaries, along with David Craven,

John Scott, Brian Kipping, Napoleon Brousseau and a dozen

other gifted young artists—all of whom would make enviable

places for themselves in the annals of contemporary Canadian art.

Steve was quiet, his sensibility was clearly rich and restless, and

his wonderfully-honed mind, as I soon discovered, ran deep and

pauselessly into inventiveness. That was over a half century ago. Like me, he’s a grandfather now, but nothing else seems greatly different.

I still remember, in vivid and seductive detail, a series of

works he made around this time. It was in 1975, I believe, that he cunningly and, it seemed, almost off-handedly, started fabricating a series of what he called “Numinous Objects.” These were small (22” x 15”) wooden panels, sturdily painted with stovepipe enamel (in dark green or navy blue with bright red frames), to the surfaces of which he would affix small scalene triangles cut from sheet brass, and screwed into place with tiny brass screws.

Armstrong says he borrowed the term “numinous” (meaning

something that arouses spiritual or religious emotion) from a book he’d been reading by philosopher and theologian Rudolf Otto) called The Idea of the Holy (1917). This was everyday reading for Armstrong; while he was making art at OCA, he was simultaneously working towards a B.A. at the University of Toronto.

Armstrong tells me he found this potentially exhausting

parallelism genuinely invigorating. While he was constructing

his Numinous Objects, for example, he was also busy reading

his way through all fifteen volumes of the collected works of

Carl Jung. Grist for the art-making mill.

The other exciting body of work I remember from so early on

involved the challenging interferences he would visit upon

a number of derelict Douglas Fir columns he had spied in a

vacant lot near the college and proceeded to drag back to the school’s big studio. The way he worked his adornments and additions to these brut columns seemed emblematic of the way he would conduct the rest of his art-making career: joyfully, wittily and always with a luxurious sensuousness that never seemed to clog or compromise the taut, conceptual focus that has always powered his progress.

He would produce Columns all along, from the first ones in

the mid-70s to works produced up until the late 1990s (a few of

them are illustrated here). Sometimes, as with Mondrian’s Column from1993, he would add something to a column’s upper corner (in this case, three small painted squares of black, red and white, arranged as a new “surreptitious” corner imposed upon the massive, natural wooden corner beneath it). Such impositions would complicate or even confound our usual understanding of the column’s true structure. For his dazzling Schoenberg’s Column from 1996, he inundated all four sides of the wooden pylon with a raucous congregation of brightly painted daubs. How did this happen? Because, as Armstrong once told me, he simply added a fugitive dab or two to the column every time he found himself using a pigment in the service of an entirely different work. It’s almost like cleaning your brush on a handy rag. Does this sound ingenuous?

Maybe, but I think it also addresses issues touching on the nature of choice, placement, order, limitation, saturation, randomness and accumulation.

In an email duologue Armstrong and I started compiling in 2017,

he wrote “I have read a lot, and looked at a lot of art, but I think

like a child. At the very least, I feel like a child when I’m

working. When I make art it is imaginary play. I’m absorbed

in it just as I was as a nine year old with my Meccano set.”

Childishness may be reprehensible, but being childlike is sublime. It’s a hallowed state. A place of beatitude. And I doubt it can be learned.

In 1977, when Armstrong’s wife, Irene, found she was expecting

their first child (they married in 1973 and, having raised

four children, are now in the fifty-second year together), Armstrong made a responsible decision that was not at all childlike: he got a job at CN. First, he was a brakeman. Then a conductor. Eventually, in 1992, he became what most kids dream about (they used to anyhow): a locomotive engineer. He worked for ViaRail until he retired fifteen years ago at age fifty-seven (he apparently had some vision problems). He’s now 73 years old.

Railroading may well have stifled a less insistent art-making

passion than Steve Armstrong’s, but it didn’t slow him down at

all. He once told me he used to scribble notes to himself

about pieces he wanted to make in the binder of track permits

hanging beside him in the locomotive’s cab, all while screaming

along the right-of-way from Toronto to Montreal. As a matter of

fact, he made so much art above and beyond his trainbound years, I never ever noticed any slackening of his production or any diminishing of quality in what he made. On the contrary. the pieces he conceived and built during these ViaRail years were richly complex and, in many cases, exacting and deeply labour-intensive. It was during this time that

he made, for example, a lot of refreshingly original paintings

on unlikely materials such as circuit boards, linoleum, pegboard,

plexiglass, upholstery fabric and corrugated fiberglass.

He was also drawing. Armstrong is a virtuoso

draughtsman, and his drawings are often about impossible,

essentially unrenderable subjects such as a newspaper clipping

(1999), a Minoan pot (1994) or—I know this one intimately well

because he gave it to me—a drawing of somebody else’s art.

The drawing in question is 24” square and was titled “Hepworth

Hors D’oeuvre” (1977). It was just what it says it was: an hallucinatorilly precise drawing of a not especially distinguished sculpture by English artist, Barbara Hepworth. The drawing is so convincing, you’d think you were staring through a window at the real thing. It must have taken forever (like twelve steady hours) to make. Armstrong tells me he never actually thought very highly of the actual Hepworth piece. So the drawing was never meant to be a homage to Hepworth. Which is what makes this brilliantly painstaking drawing so conceptually delectable: there’s a glorious absurdity in investing so

much time and effort for the huge non-payoff that so gleefully follows. The point is, the drawing is the triumph of undertaking more than it is any sort of conclusion or revelation. Not for nothing I once called him

Homo Ludens (Man who plays).

As I once wrote to him (in our Duologue), “Somewhere in his book, Real Presences (1989), George Steiner suggests that ‘in every work of art something appears that does not exist.” It’s the non-existent bits in your work that I dote upon.”

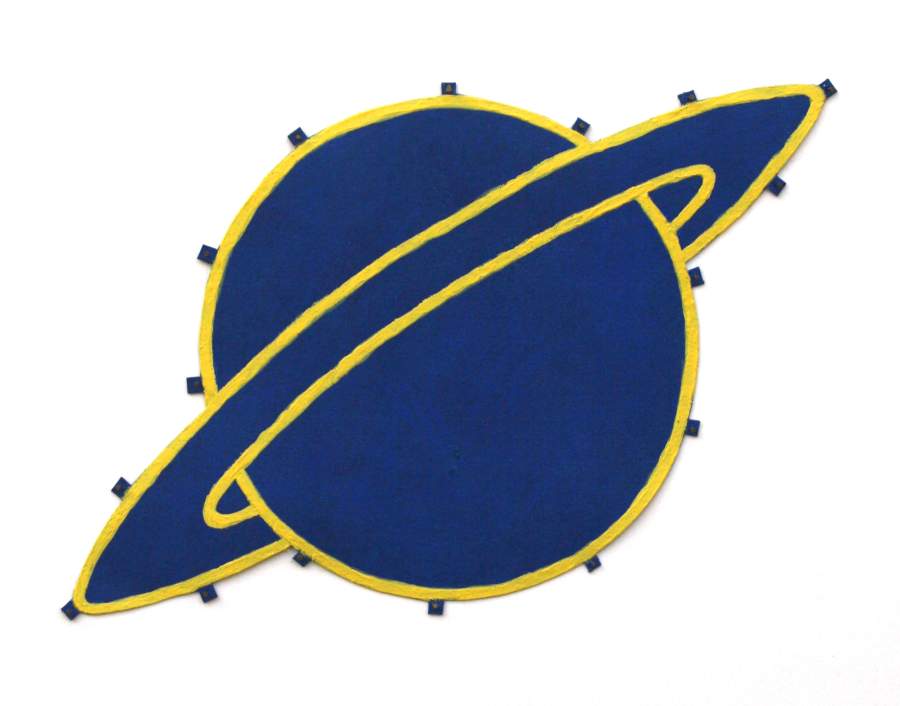

Take the planet Saturn. It always struck me as being a bit adolescent in its design obviousness. Saturn is simply too decorative. Too easy to draw. Nevertheless, Steve Armstrong has produced two or three Saturns over the years, ranging from wall-sized giants through mid-size versions (37” x 64”) to a beguiling, toy like miniature that is only 6 x 10 ½ inches,

painted on paper and nailed to the wall with tiny brass screws (reproduced here). What does he find compelling about the ringed, braceletted planet? I think it’s the very artifice I find irritating.

Armstrong loves inversion, reversal, all perceptual flickerings

between one reading of an object and its alternate possibilities. I think that for him, the way Saturn’s rings seem simultaneously flat and round (we know they are round but we draw them flat) is as intriguing as the way he delights in casting into doubt the “real” structure of a column or the “ostensible” subject of a drawing. He’s not at all interested in the child’s game of optical illusion; what he desires is the doubleness, indeed the

multifariousness of things. He likes to quote critic Clement Greenberg on how ambiguity is one of the chief sources of pleasure in art. Armstrong’s Saturns are diagrammatic, not astronomical. They are like charts or maps. In the work shown here, the planet is blue and so are its rings—except that they are not rings anymore but just one solid blue band. Both planet and “ring” are engagingly (ie unrealistically) edged in yellow. Why yellow? Why not? We read the “band” as having disappeared behind the planet, but it hasn’t; it has merely stopped when it came to the planet’s edge.

And Armstrong’s planet doesn’t float in any endless matrix of space. It is attached to the wall with these wonderful miniature brass nails—which I find just as entrancing now as I found the brass screws nailing the brass triangles onto his Numinous Objects from 1975. Brass nails? Now Saturn is jewel-like.

Well, we see what we see. But we imagine a lot more. And it is in that perceptual wedge between what we see, what we think we see and what we think we know that is the locus of Steve Armstrong’s brilliant, searching, inexhaustible art.